The production and distribution of Shaker medicines was a cooperative operation, dependent upon relationships with commercial entities. The Shakers grew the plants and made the medicine from plant extracts. Packaging such as bottles, boxes, and paper inserts were commercially produced and shipped to the Shakers; the Shakers bottled the medicine, packaged the product, and sent […]

The production and distribution of Shaker medicines was a cooperative operation, dependent upon relationships with commercial entities. The Shakers grew the plants and made the medicine from plant extracts. Packaging such as bottles, boxes, and paper inserts were commercially produced and shipped to the Shakers; the Shakers bottled the medicine, packaged the product, and sent batches of it to distributors.

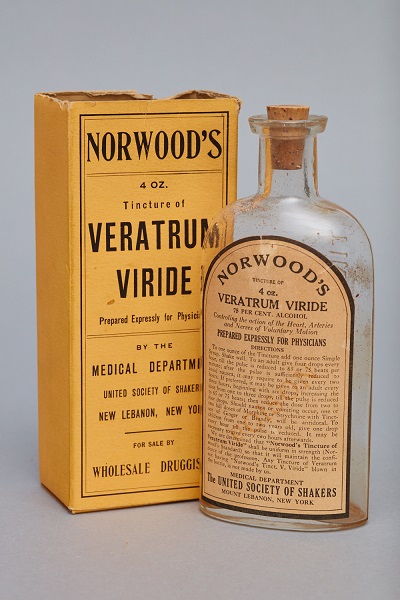

The Shakers produced a medicine called Norwood’s Tincture of Veratrum Viride from the 1850s until the 1930s or 1940s. As late as 1936, the Mount Lebanon Shakers published a booklet on the history, use of, and endorsements of the preparation.

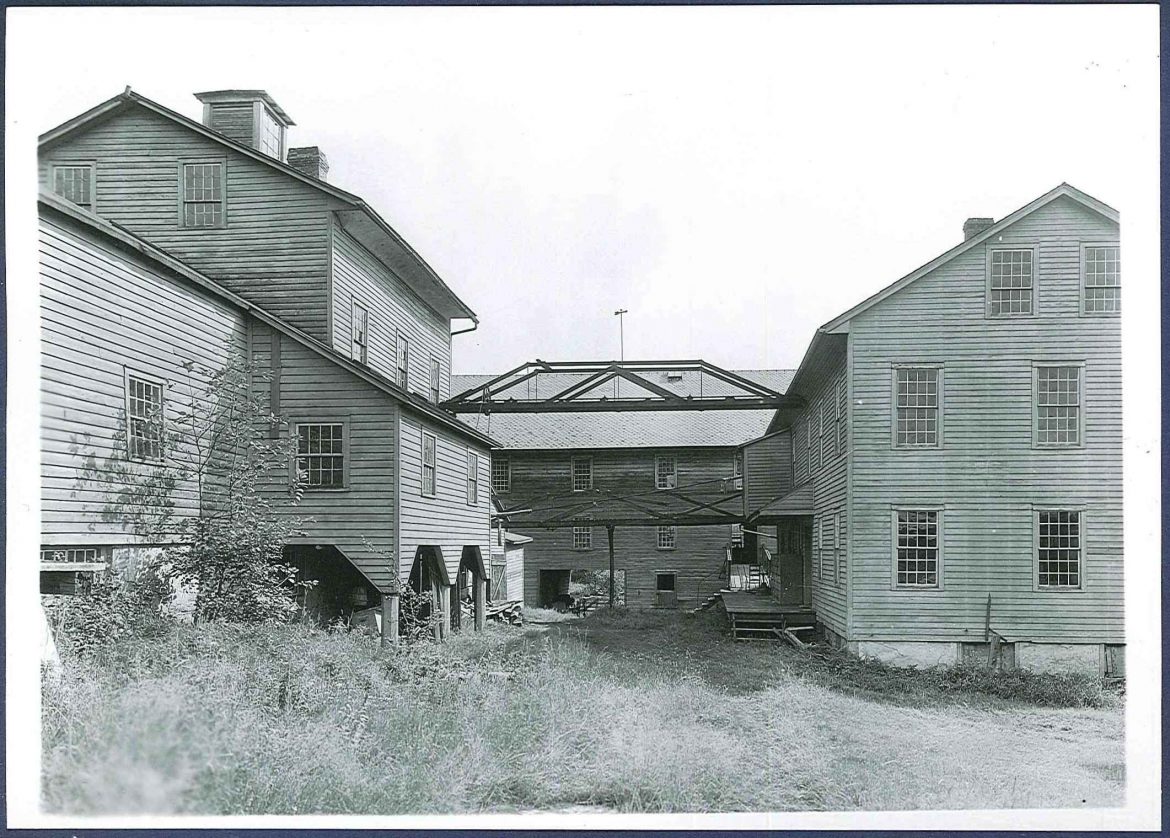

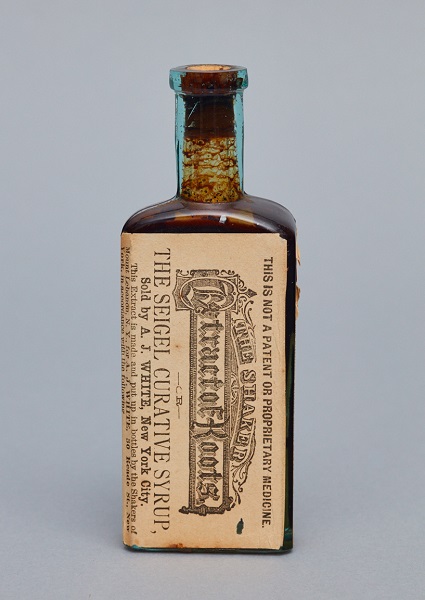

Along with a medicine distributed by A. J. White under the name of Mother Siegel’s Curative Syrup or the Shaker Extract of Roots, the production of medicine was a major industry for the Mount Lebanon Shakers, particularly after the catastrophic fire of 1875, which destroyed eight buildings at the Church Family, including the Herb House. Trustee Benjamin Gates, seeking to quickly recover the family’s finances, made an agreement with A. J. (Andrew Judson) White to manufacture medicine which White would distribute through a network of agents. It became one of the most common medical remedies in the country, and was sold in numerous other countries as well.

Journals kept by the Shakers illustrate the time and personnel needed to maintain their output, as well as the breadth of its distribution. For example, in 1879, batches of medicine were shipped to India and Australia. One journal, “A Domestic Journal Kept by Order of the Deaconesses, 1879-1882,” records that in 1879, the 48 sisters of the family spent 550 days working on medicine production and packaging, suggesting an average of eleven working days per sister; in 1880, it was 447, and in 1881, it was 1,250 days (an average of 26 working days per sister).

This journal also documented the problem of depending upon outside suppliers. On May 4, 1880, Sister Anna Dodgson wrote in the deaconesses’ journal that, “We are not employed in the Medicine department at present – waiting for glass.” Again, on July 21, she noted, “We commence again on medicine,” and added, “We are troubled to get bottles.” On October 6, she wrote, “We have pressing orders for Medicine.” While that entry does not indicate that a lack of bottles caused the orders to be delayed, the problem arose again in December. On the 19th, Sister Anna wrote, “We have passed two very quiet weeks since my last [entry]…. We are still without bottles, so no medicine business is going on.”

By the 21st of December, they were able to “Commence again on the medicine.” But by the 23rd, she wrote that a group of Shakers travelled “to the glass works,” perhaps to order more bottles. On January 27, 1881, it seems the Shakers were forced to find a new supplier; Sister Anna recorded, “B. G. [Trustee Benajmin Gates] takes the molds of the bottles we use from White, the glass blower on the flat [Lebanon, N.Y.], and goes somewhere to get bottles. [They say] White has failed.”

By February 1, the situation appears to have been resolved, for Sister Anna wrote, “We are driving at our medicine. We have failed entirely in getting bottles on the flat, [and] we hope to be troubled no more.” It took a considerable effort; on February 4 she wrote, “We rally all hands to the medicine…. 14 on Thursday and 12 on Friday. But we get the order off.” On July 30, 1881, she wrote that, “The medicine business is still pressing, not less than 6 Sisters are constantly employed, often more. Henry Clough is in the department, and Joseph Bird in the Laboratory. This of course makes it harder for the hands at home.” Production of medicine continued until, on August 25, 1881, Sister Anna stated, “We have now a prospect of a short vacation, the first stop on the medicine since November,” although, by that point, she added, “now we run three Medicine Departments.”