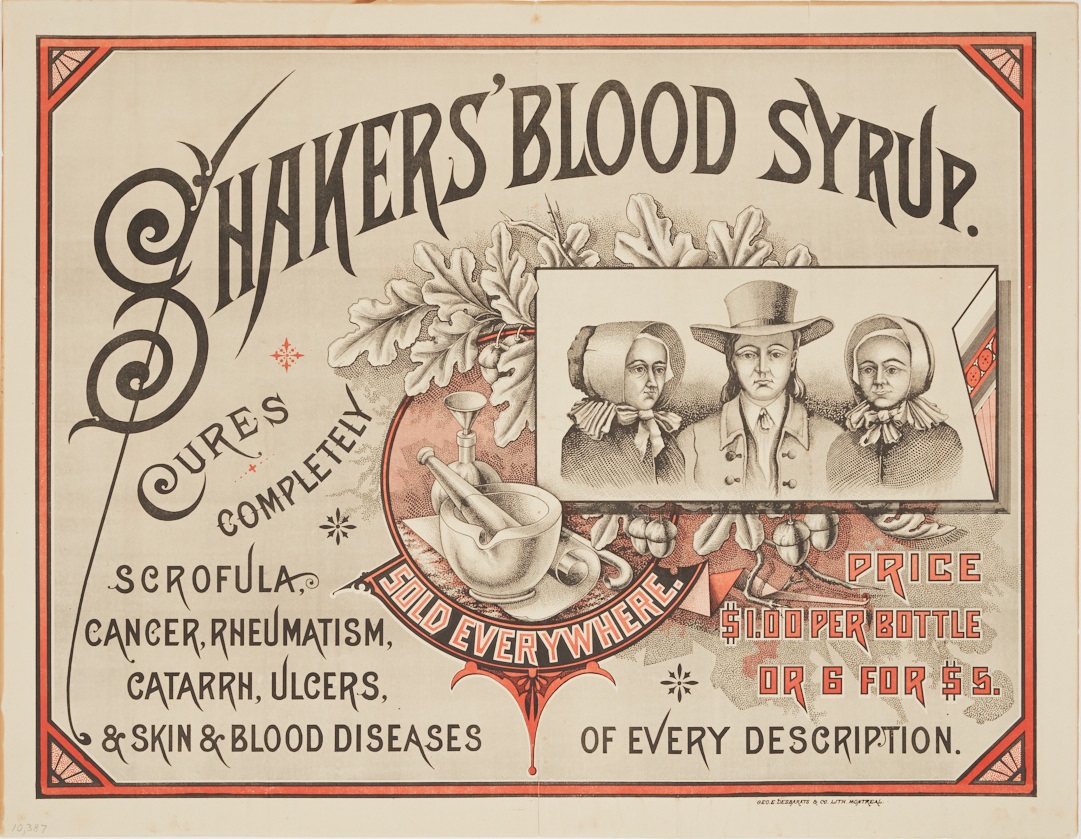

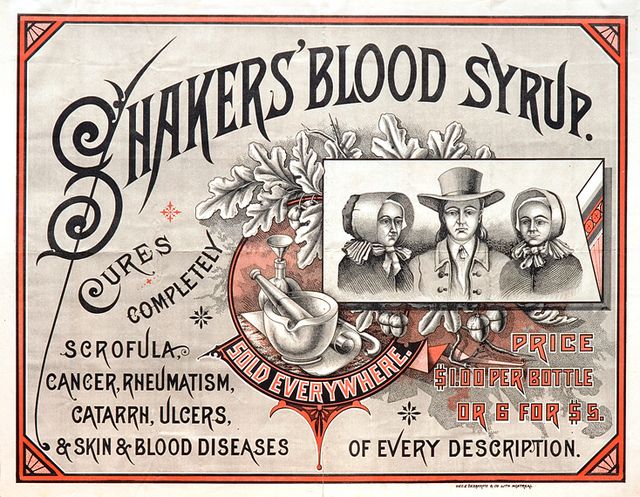

Advertising poster for Shakers' Blood Syrup. Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon 1957.10387.1.

The poster, printed in black and red, shows an illustration of two Shaker sisters standing on either side of a brother. The text proclaims, “Shakers’ Blood Syrup cures completely scrofula, cancer, rheumatism, catarrh, ulcers, & skin & blood diseases of every description.” The medicine, however, was not made by the Shakers, and the society had […]

The poster, printed in black and red, shows an illustration of two Shaker sisters standing on either side of a brother. The text proclaims, “Shakers’ Blood Syrup cures completely scrofula, cancer, rheumatism, catarrh, ulcers, & skin & blood diseases of every description.” The medicine, however, was not made by the Shakers, and the society had not authorized the use of their name or image.

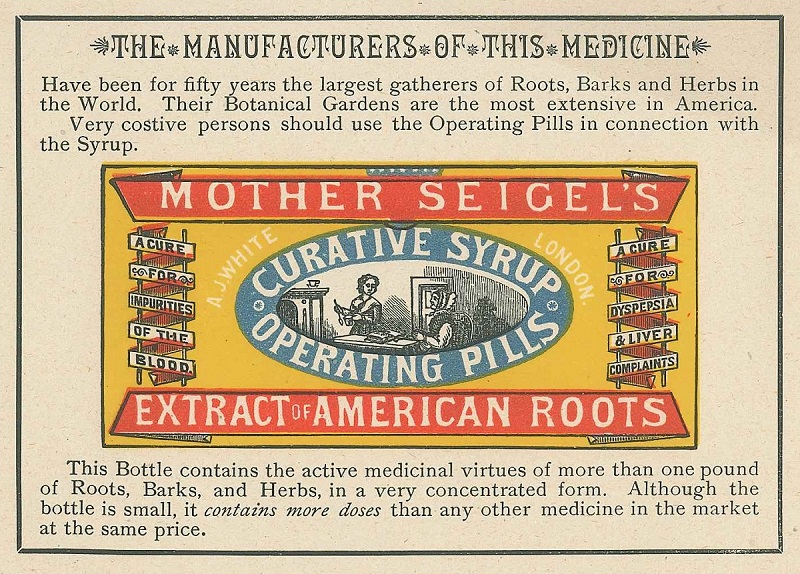

The syrup’s purported indications bore a strong resemblance to the preparation sold as The Shaker Extract of Roots or Mother Seigel’s Curative Syrup, which was manufactured and bottled by the Shakers and distributed by A. J. White. A label for the Extract of Roots calls it “A cure for impurities of the blood” and “A cure for dyspepsia & liver complaints,” and promotional materials further claimed that it fully cured “diseases of the liver and bowels, diseases of the stomach, rheumatism, heart disease and skin ailments,” much as the Blood Syrup claimed.

It is not clear when “Shakers Blood Syrup” was first produced or marketed, but the Shakers became aware of it by at least the summer of 1884. In a journal kept by the deaconesses of the Church Family, Sister Anna Dodgson wrote on August 17, “[Benjamin Gates, society trustee] leaves for Canada to meet Dr. White who is in trouble with a counterfeiter of his medicine &c.” According to another family journal, Brother Benjamin returned on August 26. No more is mentioned of the matter in Shaker journals for the rest of 1884, but it began to receive some public attention. On October 2, a newspaper notice stated, “A dispatch from Montreal says that the Shaker society at New Lebanon is about to institute proceedings against Smith Bros & Co Montreal, for $50,000 damages for infringement of a patent. It is claimed that the defendants illegally manufactured and sold syrups bearing the name of ‘Shaker Blood Syrups’ the trade-mark of which they had patented at Ottawa on stating that they were the first to make use of it, while in truth it was the property of the United Society of Shakers.”

A month later, on November 14, The National Druggist, published in St. Louis, stated, “Smith Bros. & Co., of Montreal, a concern of recent origin, who started the manufacture of ‘Shakers’ Blood Syrup,’ have failed, and one of the partners is reported missing. Their liabilities are stated at over $10,000. The ‘Shaker’ community (sic) has recently issued an action against the firm to restrain it from using their name, etc., in connection with such preparations made in Montreal.”

On January 20, 1885, Anna Dodgson wrote in the deaconesses’ journal that “B. G. [Benjamin Gates] leaves for Canada to settle some business in regard to the trademark on Mother Siegel medicine taken by fraud by Smith Brothers.” On January 27, A. J. White, Ltd.’s office issued an announcement that stated:

As soon as [the Blood Syrup] came to the knowledge of the Shakers… [P]roceedings at law were taken by the Shakers, charging the [Smith Bros.] firm with fraudulently using and stating without authorization in their pamphlets that this medicine was prepared by the Shakers. Shortly after this action was taken, the firm in question became insolvent. On the 24th January [1885], Smith Bros. signed a declaration or agreement in which was contained, among other things, the following: ‘And whereas the said Smith Bros. now admit, and by these presents do admit that they have no right to the said trade mark, or to sell medicines as Shaker preparations… And that the said action of the Shakers Society as taken against us for the cancellation thereof is well founded….’ The Shakers upon this agreement being signed withdrew their action against Smith Bros.

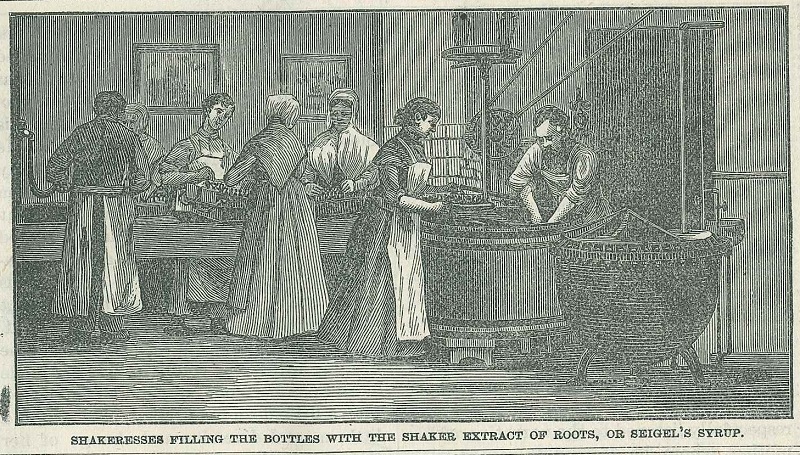

Meanwhile, the Shakers had become concerned about boosting the sales of both medicines and garden seeds. On July 1, 1884, the official Church Family record noted that, “An artist from New York is here sketching some pictures of our extract laboratory and works, and the medicine buildings & rooms, for Dr. White to publish in a pamphlet, of which he contemplates having about six million copies of printed & circulated throughout the United States and Mexico, and, I believe in Europe.” And on January 1, 1885, the record stated, “Efforts are being made to revive seed business by instituting improved seed boxes, and seed bags printed in Chromo., &c. &c. Proprietors [of the medicine business] are introducing new improved labels and printing 20,000,000. Advertising pamphlets using over 100 tons of paper, and employing several hundred hands day & night.” Several years before, the Shakers had begun publishing an almanac to promote the Extract of Roots. The 1885 edition of the almanac included a series of engravings showing the Shakers at work producing and packaging medicines. Perhaps, in addition to reinvigorating sales, the Shakers were attempting to reclaim control of how their image and reputation were presented to the world.