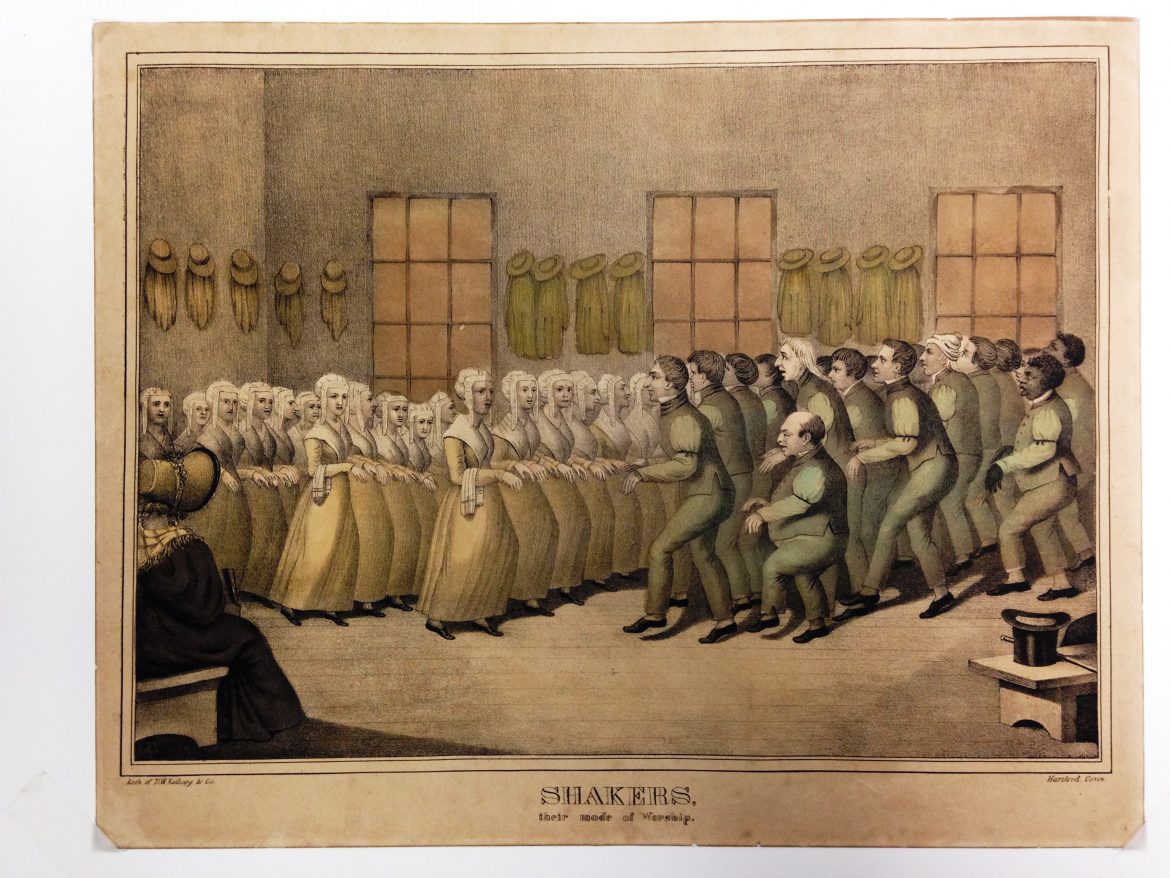

Hand-Colored Lithograph, “Shakers. Their Mode of Worship,” D. W. Kellogg & Co., Hartford, CT, Ca. 1833/34-1840, Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon: 1958.10574.1

Around this time last year, we looked at this illustration of the Shakers’ worship and suggested that as research on the Shakers continues there is an opportunity to bring forth the personal stories of more and more of those who lived that unique committed life. At that time we explored the possibility of identifying several […]

Around this time last year, we looked at this illustration of the Shakers’ worship and suggested that as research on the Shakers continues there is an opportunity to bring forth the personal stories of more and more of those who lived that unique committed life. At that time we explored the possibility of identifying several of the Shakers portrayed in the illustration – specifically the short Shaker brother and the two brothers presented by the artist as persons of color. (In previous research on this topic and generally in research about racial inclusion among the Shakers, these brothers are identified as African-American; however, the Shakers were often not specific in describing the race of individual members, so they are referred to here as persons of color.)

Hand-Colored Lithograph, “Shakers. Their Mode of Worship,” D. W. Kellogg & Co., Hartford, CT, Ca. 1833/34-1840, Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon: 1958.10574.1

Sometime around 1830 an unidentified artist sat with other world’s people who had gathered for the public meeting in the Mount Lebanon Shakers’ new meetinghouse and produced a sketch of the Shakers’ “mode of worship.” Once the sketch was engraved and printed for public sale it became the first published image of the Shakers. It was apparently “wildly popular” and “was copied with only slight alterations for years thereafter, appearing variously as lithographs, woodcuts, and engravings. It was such a popular subject that at least eighteen versions of the same scene are known to have been published in the nineteenth century,” according to Robert P. Emlen, author of a study of these prints published in Imprint: Journal of the American Historical Print Collectors Society in 1992. This print and those eventually derived from it have been used by scholars in studies of Shaker dance, costume, and architecture. Because the artist, possibly overwhelmed by the novelty of the scene, included persons of color among the brothers, the print has been used to document and emphasize the Shakers’ acceptance of all races into their church – as equals. However, the experience of life as a Shaker of color has yet to be well documented or analyzed.

Hand-Colored Lithograph, “Shakers. Their Mode of Worship (detail),” D. W. Kellogg & Co., Hartford, CT, Ca. 1833/34-1840, Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon: 1958.10574.1

Whatever the artist’s motivation for including these two brothers, it offers an interesting opportunity to explore and hypothesize about who these two men may have been. Some years ago the short brother in the ranks of the brethren was posited to be Brother David Rowley, a 50 year-old 4’10 3/8″ brother who was a resident of the Mount Lebanon North Family. As Brother David’s stature was useful in putting a name to an otherwise anonymous member of the sect, the consistent representation in nearly all of the known versions of this scene of these two brothers as men of color challenges us to know who they were. Probably fewer than a dozen of the more than 3000 Shakers who have been identified as residents of the Mount Lebanon community over the years have been identified as persons of color. The date of the sketch helps narrow down the possibilities. At this time members of the Church Family would probably not attend the public meeting so those present were likely from one of the novitiate families – the North Family or the Upper and Lower Canaan Families. Occasionally members of the Second Family or the East Family might attend. Surveying the list of known Mount Lebanon Shakers who were identified by the Shakers as persons of color and who were members of one of the novitiate families, or the Second or East Families, around 1830 produces only five possible candidates.

Brother Tower Smith was a member of the North Family. In August, 1821, North Family Elder Calvin Green recorded in his journal that, “The Brethren reap & stack the rye on Amos’s mountain … a Black man from Hudson here, by name of Tower Smith, wants to live with us — he had some faith years ago. We finish pulling flax.” Little additional information about Brother Tower’s life at the North Family has come to light. In October 1833, in a shifting of members’ rooms to provide accommodation for the sick and aged in the dwelling, Brothers Frederick [Crosman], John [Wood], and Tower [Smith] were moved into a room, previously used for the spinning jenny at the North Shop. Six months later it was noted in “A Brief Journal Kept by R[ichard] Bushnell,” in the collection of Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon, that “Abel [Knight] goes to Hudson, taking with him Tower Smith, who like most others, wants to be with those who were most congenial to his sense & state.” Elder Richard added, “poor old man I hope he may not spend the remainder of his day in suffering.”

Brother Ransom Smith was apparently the son of James and Sarah Smith. According to Elder Calvin Green at the North Family, James Smith arrived in New Lebanon, on February 5, 1816, and left two loads of goods before returning to his home in Norwich, New York, on the 9th. He returned at the end of February with “2 of his Daughters, viz. Jerusha & Sally,” leaving them with the Shakers when he returned home at the beginning of March. On June 7, that year, “James Smith with his family arrives here [at the North Family] having moved at length & go to the old Patterson house,” a farm house just west of the North Family where the Shakers housed new arrivals. A week or so later, James and Sarah’s son, Ransom, arrived at the North Family with what was probably the last load of the family’s belongings. Ransom lived at the North Family until being moved to the Second Family after Christmas, 1835. He lived out his life as a Shaker, dying at the Second Family at the age of 81 in 1876. As a Shaker he worked as a teamster and a gardener.

Brother Abraham Wood attended school at the Church Family in 1823 at the age of fifteen. In April, 1824 he came from Frederick Crosman’s family and went to live at the Upper Canaan Family where he remained until January 6, 1828 when it was noted in “A Journal or Memorandum for the Family of Believers [at Canaan]” in the collection of the Library of Congress, that “Abram Wood goes to the world.” Apparently he reconsidered this decision and on January 1, 1830 the same journalist noted that, “[Albert Whittemore] age 34 from Mansfield Connecticut, came in on the 26th of last month, & unites at, or about this time.” But five days later it was noted that “the above named Albert Whittemore is found to be Abraham Wood, who lived in the family of Frederick Crosman & Aaron Bill about nine years ago, on the discovery of which he peaceably goes away.” Brother Abraham’s (or Albert’s) candidacy as one of the African-American brothers included in the print is weakened by his absence from the community from June, 1828, until November, 1830, but since the exact date of the visit by the artist has not been verified, his inclusion is not impossible.

Brother James Taylor came to the North Family in the summer of 1816 and professed his faith. In June of that year he was sent to live at the Upper Canaan Family. He is noted by a journalist on January 1, 1832 in “A List of the [Upper Canaan] family, with their respective ages,” as being 41 years old, having been born in 1791. On November 16, 1835, in the same journal, detailing events at the Upper Canaan Family between 1813 and 1843 in the Shaker Collection at the Library of Congress, it is noted that, “James Taylor (man of color) goes to the world, he was rec’d as a candidate (according to recollection) Feb. 1829 – lived with C[illegible] Bryant in the Hill house & received into this family some time in 1831.”

Brother Nelson Banks was born in Stafford, Connecticut, January 5, 1800. Although it is not clear when he made the decision to unite with the Shakers, he apparently had a somewhat successful life prior to making that commitment. He signed the North Family covenant on April 13, 1829 and on December 19, 1831 “deposited in the hands of the Trustees eight hundred and twenty nine dollars and took a certificate of inventory.” This money, as noted in the North Family Book of Records in the collection of the Library of Congress, “he freely gives for the benefit of the North Family in the United Society (Called Shakers) in New Lebanon without any change or demand to be made by him for the use of the same so long as it is in the employ of said family.” This standard agreement made with new members allowed them to deposit funds for the use of the family without fully consecrating the money to the Church. Members who had signed this kind of document could request the return of the money or property if they decided to leave, but Brother Nelson stayed, and on June 13, 1837, “dedicated & devoted to the united interest of the North Family eight hundred & twenty dollars said money being the same deposited in the hands of the Trustees in the year 1831 December 19th for which he then took a certificate of inventory: which is now canceled by his choice & dedication.” Two years later Brother Nelson moved from the North Family to the Second Family where he lived out his life a Shaker primarily as a gardner, dying August 19, 1878 at the age of 78.

Although these are the only identified men of color (so far) at Mount Lebanon who appear to be possible attendees at a public meeting in the Mount Lebanon Meetinghouse during the time when the visiting artist was able to make the sketch, the Shakers were not particularly concerned about identifying a member’s race as part of their official records. Usually this information is discovered as Shaker records are studied with a specific interest in the topic.

As useful as this print is in visualizing Shakers and Shaker worship, the addition of some personal stories of those captured by the artist at that moment only enlivens its importance in telling the Shaker story. Next up – the brother wearing the stocking cap during meeting – there must be a story behind that.