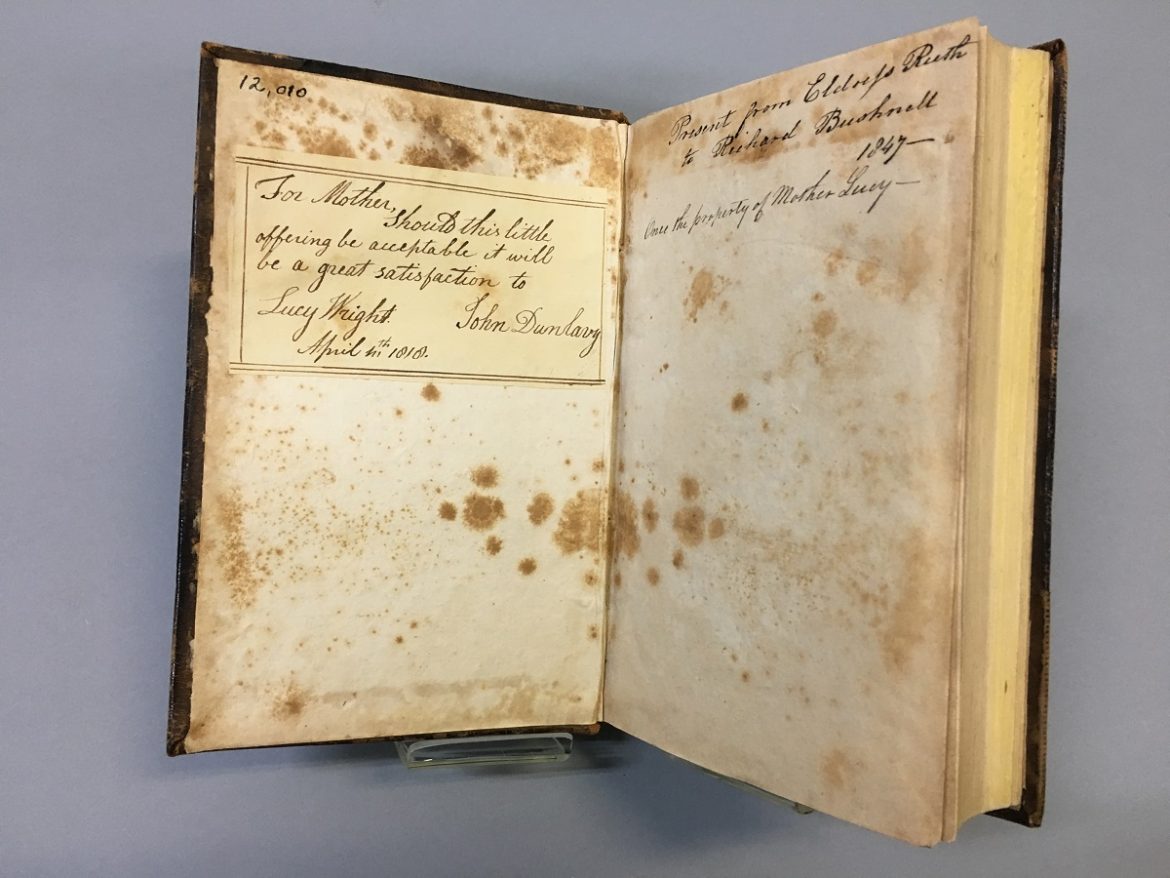

"The manifesto, or, A declaration of the doctrines and practice of the Church of Christ," inscribed to Mother Lucy Wright.

March is Women’s History Month; in honor of this, we offer a look at the life and accomplishments of Mother Lucy Wright, the leader of the Shakers from 1796 to 1821. During her twenty-five years in power, the Shakers gathered seven new communities and experienced the greatest gain in converts the society would ever have. […]

March is Women’s History Month; in honor of this, we offer a look at the life and accomplishments of Mother Lucy Wright, the leader of the Shakers from 1796 to 1821. During her twenty-five years in power, the Shakers gathered seven new communities and experienced the greatest gain in converts the society would ever have. Under her leadership, important works such as John Dunlavy’s Manifesto, or, A declaration of the doctrines and practice of the Church of Christ, seen above, were published, and she created many of the rules and regulations that governed daily life in order to foster the communal bonds of union necessary for the stability and endurance of the Society.

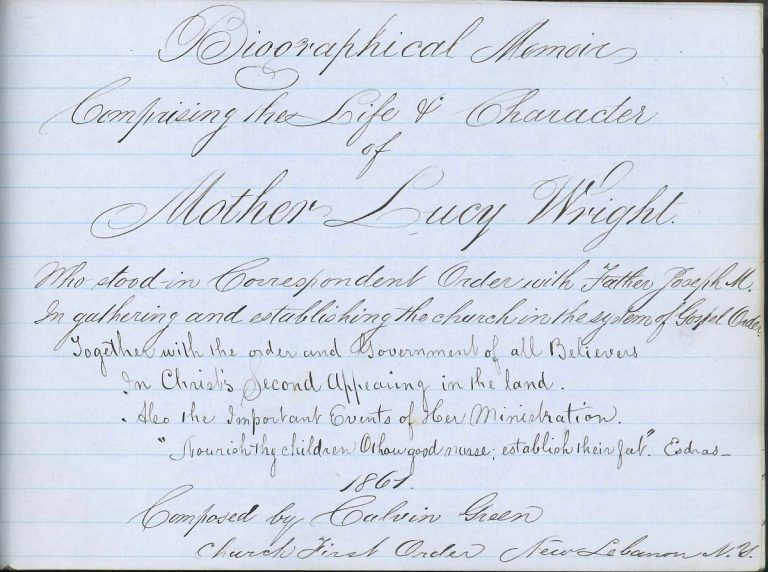

Few writings by Mother Lucy survive; perhaps the best source of information about her is the Biographical Memoir composed by Elder Calvin Green in 1861, forty years after Mother Lucy’s death. But Elder Calvin, born in 1780 and raised at Mount Lebanon, knew Mother Lucy well. Though far from objective, he captured the strength of her character and the shrewd intelligence with which she guided the Shakers.

From an early age she demonstrated remarkable qualities. In 1780 she traveled with her husband, Elizur Goodrich, to visit Mother Ann Lee, founder of the Shakers, at Watervliet. Elizur quickly converted, but Lucy was more reserved. Nonetheless, Mother Ann told Elizur that to have Lucy join would be “equal to gaining a nation.” Lucy did convert, and soon after was chosen by Mother Ann to take charge of the sisters at Watervliet while Mother Ann and the elders embarked upon a missionary journey in 1781. According to the testimonies of Believers gathered in 1816, however, she was with Mother Ann at the “Square House” at Harvard in August of 1782. There a mob came and threatened violence. As Elder Henry Blinn put it in 1887:

Lucy Wright, a young sister, stood fearless before them, and endeavored, by kind and gentle words, to calm their ferocious spirits, informing them that Mother Ann and the Elders were not in the house. Her words to them were idle tales, and they refused to listen. They even threatened her with violence unless she remained quiet. From this interview the Believers understood quite well the object of their search, and Lucy immediately planned to escape from the place. She informed Mary Partington of the case and then taking some milk pails, they passed safely through the mob on their way to the barn, ostensibly for the purpose of obtaining some milk. Safely within the barn, the pails were carefully laid aside, and the two sisters took their flight across the fields….

When Father Joseph Meacham took over leadership of the Shakers after the death of James Whittaker, one of his first acts was to name Lucy as his co-lead. Father Joseph is crediting with devising and implementing much of what defines Shaker life, from the structuring of Believers into families and orders to the designation of elders and eldresses to manage the spiritual affairs and deacons and deaconesses to oversee temporal matters. Yet from the time he called upon her to move from Watervliet to the meetinghouse at Mount Lebanon to join him in 1788, he worked closely with Mother Lucy. In a letter he wrote to her just before his death, he stated that the success of the community was the product of their “joint union & labours.” In that letter he named her his successor, writing, “Thou, tho of the weaker sex… will be the Elder or first born after my departure.” The naming of a woman to a leadership position was not at first universally accepted by the Shakers; Elder Calvin Green alludes to “many erroneous sentiments to correct,” but states, “Thus it was that these things caused much labor and extreme tribulation upon Mother Lucy; but by her wise and discreet conduct & by Father Joseph’s counsel in due time she gained the confidence of all concerned, and was freely acknowledged by the general union of the members as a Mother indeed.”

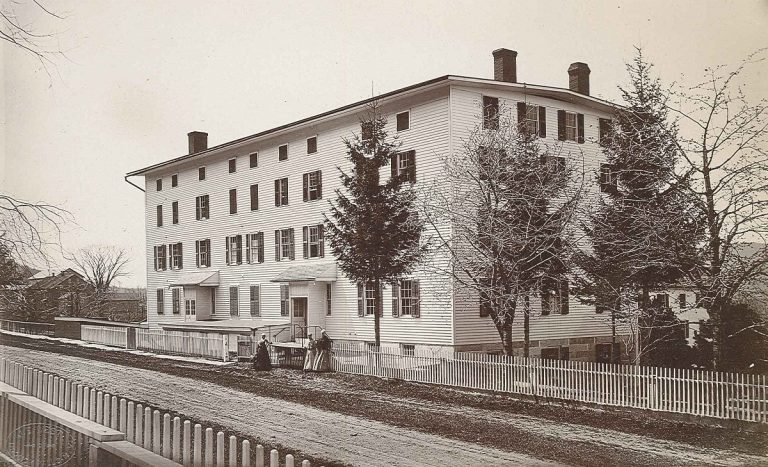

She came to leadership faced with the loss of many converts due to apostasy, and devised an effective solution: the establishment of novitiate or gathering orders “for the purpose of laboring with & initiating those who were or might be prepared to receive the Gospel.” At Mount Lebanon, the “North House” and an area of land was designated for this purpose; this later became known as the North Family, the historic site currently stewarded by the Shaker Museum. The elders and eldresses of the gathering orders were those most gifted in gathering potential converts, and life in the gathering order was designed to habituate novitiates to Shaker life before moving to the inner orders of the community.

Photograph showing the first dwelling house of the North Family, Mount Lebanon. It was built in 1818, after Mother Lucy Wright designated what would become the North Family as a gathering order. Shaker Museum | Mount Lebanon 1955.7468.1

The gathering orders proved to be successful. But the bolder and more significant decision made by Mother Lucy was to resume missionary efforts. She sent several of the society’s best speakers, including Benjamin Seth Youngs and Issachar Bates, on journeys through New York and New England; according to scholar Priscilla Brewer, the population of the eastern societies increased by more than 42% from 1800 to 1820. In 1805, having observed the beginnings of what is now known as the Second Great Awakening, a broad Protestant revival in the United States, she sent them westward. Their travels in Kentucky, Ohio, and Indiana resulted in the founding of seven more communities, raising the number of villages from 11 to 18.

Mother Lucy devoted a great deal of attention to making rules and regulations, which were put into writing shortly after her death under the title “Millennial Laws.” Few things seemed too small to attract her notice; according to a Watervliet journal, just before her death she “visited round among the sisters, and very carefully examined their work & working apartments,… critically observing all as she moved around.” According to Elder Freegift Wells, she once declared, “You ought never keep your hands behind you as a common practice, the place for the hands is before, not on your backs. I hope this ridiculous practice of walking about in this manner may be left off.” Mother Lucy also frequently spoke out against unrefined speech, and the use of the words “yes” and “no” instead of “yea” and “nay.”

The rules and regulations put into place during this period reflect her attention to detail. Some might be seen as trivial, such as a prohibition against leaning back in chairs, or forbidding brothers and sisters passing each other on staircases. Yet they reflect her concern for, and accomplishment of, promoting greater integration and thus stronger communal union among thousands of individuals in villages spread over a great distance. It was during her administration that uniform standards of dress were put into place to prevent vanity or jealousy. Her interest in refining the speech of Believers led to the appointment of Seth Wells as the head of Shaker schools, which eventually gained a reputation for excellence.

She also spoke frequently and powerfully in worship meetings on the importance of union. At Watervliet in January of 1820, she told Believers, “You must labor to be of one heart & one mind & all strive together….” In August of 1820, she said in the Mount Lebanon meetinghouse, “The gift of union is a great strength. It is always a very necessary gift for believers. A family or society that are united can increase and prosper in things spiritually & temporally but if they are not agreed they are like persons working against each other…. To be loved is to love, & to be blest is to bless, & if you cannot love & bless you cannot be united.” She also expressed the sense of union and love she herself felt for Believers, telling the Mount Lebanon Shakers in June of 1816 that, “I feel for you all. You are my interest, & I am yours.”

In January of 1821, she returned to Watervliet, expressing the desire to, as Elder Calvin Green put it, “finish her work in time in that place and have her earthly body buried in the same ground” as Mother Ann and Father William. In her last public address, on January 21, she said, “How miserable a person must feel without friends; all people want union and friendship, and if we cannot conduct in such a manner as to gain friends, we find a hard travel, indeed. Union is more valuable than all earthly things….” She died on February 7, naming as her successors in the ministry an elder and eldress. Never again would a Shaker bear the responsibility of leadership alone, or hold the title of “Mother.”